International justice mechanisms in Kosovo are righteously perceived—and as the data shows—as biased, directed primarily against Kosovo Liberation Army in their efforts to examine war crimes and crimes against humanity in Kosovo. UNMIK and EULEX issued 48 indictments, 16 against Albanians, 13 against Serbs and four indictments against Montenegrins, indicted 61 Albanians and 44 Serbs, and convicted 34 Albanians as opposed to four Serbs and one Montenegrin. And, while the Specialized Chambers of Kosovo in The Hague begins the trial against the former heads of state, the vast majority of mass murders—out of an estimated 186 mass murders committed in Kosovo—remain unresolved.

AS KOSOVO and Serbia make the final struggles to normalize their neighborly-relations, many Albanians criticize Prime Minister Albin Kurti for his willingness to accept the EU Proposal-Agreement—through which—Kosovo agrees to “overcome the legacy of the past,” giving up her quest to sue Serbia in an international tribunal. If Serbia accepts—and fully agrees—to implement the proposal, it would further advance toward the EU membership—without resolving thousands of internationally recognized crimes perpetrated by Milosevic regime in Kosovo (and in the territory of former Yugoslavia), without apologizing and without providing remedies and reparation measures to victims and the affiliated, and without addressing the issue of the missing persons from the war. As of today, 1,617 individuals, predominantly Albanians, are unaccounted for—alongside with 9,876 belonging to other nationalities—who disappeared during or as a result of wars in the region. The resolution of the missing persons’ whereabouts is determinant for achieving peace and reconciliation with Serbia, which families are NOT willing and ready for—until they receive truth and justice for each and every one. Of their beloved. Ultimately.

The overwhelming majority of mass murders, on the other hand, remain unresolved. None of the mass murders out of an estimated 186 mass murders carried out in Kosovo, except for mass murder in Krushe e Vogel and Recak, had been investigated or tried by international justice mechanisms in Kosovo, UNMIK (UN Mission in Kosovo) and EULEX (EU Mission of Rule of Law). None of them except for Krusha e Vogel, Izbica and Meja, were included in the International Criminal Tribunal for former Yugoslavia’s (ICTY) indictments against Milosevic et al. and Milutinovic et al., nor were they investigated or tried by Serbia Office of the War Crimes Prosecutor (OWCP). In most cases, such as the mass murder of Meja and Korenica, the authors of crimes, as BIRN’s Serbeze Haxhiaj revealed, are known to local people and live free in Serbia, Montenegro or Slovenia; they never been prosecuted despite the existing evidence and the witnesses’ testimonies submitted to the ICTY. Some of the survivors have been waiting for 20 years, with some even dying, without having a chance to testify to the court,meaning, as Haxhiaj suggests, that the perpetrators are unlikely to ever face justice.

25 years since the mass murder of Qirez and Likoshan and the mass murder of Jashari family in Prekaz i Ulët, meanwhile, no one has ever been investigated or tried for these crimes—both constituting war crimes and crimes against humanity under international law. UNMIK and EULEX never initiated an investigation nor did thesecases appear in the ICTY’s indictment against Milosevic et al. and Milutinovic et al., let alone being investigated or tried by Serbia justice institutions. And, while the murder of Jashari family is under the investigation of Kosovo Special Prosecution Office, Hamdi Sejdiu’s quest for justice (for his four brothers tortured and executed through February 28—March 1st, 1998, in Qirez) has been turned down by three instances of justice on the grounds that Kosovo’s judicial institutions have no power to bring another state, Serbia, to the court.

International transitional justice mechanisms have collectively failed to prosecute and adjudicate war crimes and crimes against humanity in Kosovo. Serbia, from its part, has made little or no progress to addressing impunity and bringing to justice suspects of criminal responsibility. Accountability, truth and justice remain ideals rather than reality in the region, BIRN concludes in a book, After the ICTY: Accountability, Truth and Justice in the Former Yugoslavia, published in 2020. Regional cooperation is at its lowest level in years. There is a stagnation and a significant fall in the number of new cases launched. No charges involving complex cases and high-level perpetrators—with only a few middle-to-high-ranking officers indicted so far. The number of indictments, as Humanitarian Law Center in Serbia (HLCS) suggests, has continued to decline: fewer suspects indicted and fewer victims named (2019). The EU Commission criticized Serbia for “weak records,” blaming the government for showing “no genuine commitment to investigating and adjudicating war crimes cases,” particularly complex and high-ranking officials cases, while demanding to prioritize these cases and provide a clear legal approach to resolving the issue of command responsibility.

Whereas the practice of impunity in Serbia prevails, Kosovo, on the other side, was forced to set up the Specialist Chambers, the fourth international transitional justice mechanism to prosecute and adjudicate war and post-war crimes, and the first hybrid court”directed primarily, although not explicitly stated, against one militarized ethnic group,” the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). And whilst, the former President of Kosovo Hashim Thaci, the first sitting head of state indicted from a hybrid court, awaits the beginning of the trail in Specialist Chambers in The Hague, Serbia high rank perpetrators walk free—without being disturbed from justice. Created under the international pressure to deal with the supposedly KLA unpunishable crimes, the Specialist Chambers is viewed by Kosovo Albanians and Serbs more as a political rather than a legitimate instrument of justice; a mechanism, which will, most likely, deal with the same set of crimes and defendants, suggesting, as some authors argue, that international community is willing to create as many judicial mechanisms as necessary to achieve its anticipated results—regardless of the costs—and at the expense of Kosovar people needs and wants.

In Numbers: The Indicted and the Convicted Albanian vs. Serbian Defendants

“…Serbian regular forces kidnapped a girl from a nearby town in Suva Reka, they raped her and cut her throat and left her naked in the tall grass to die. Barbarities of this kind have been ongoing on for thousands of years, but it was not until this century that a mechanized army carried out such crimes in the service of its government. That is genocide; the rest is just violence. And, whenever I read stories of Albanian atrocities that confuse the two, I think about that girl in Suva Reka and all that it took to bring about her death.” Sebastian Junger, Lives; A Different Kind of Killing, New York Times, February 27, 2000.

THE INTERNATIONAL community at large and the international transitional justice mechanisms in Kosovo in particular are righteously perceived by ethnic Albanians—and as the data shows—as biased, directed primarily against Kosovo Liberation Army in their efforts to examine war crimes and crimes against humanity inKosovo, demonstrating a tendency to balance the victim with the perpetrator. Based on the existing data, the number of Albanians/KLA members prosecuted, tried and convicted by UNMIK and EULEX is higher comparable to Serbs/members of armed forces, considering the balance of forces and the magnitude of crimes committed by Serbia and the Former Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) forces versus the KLA members. (The number of convicted Albanian and Serbian defendants from the ICTY is equal: five from each side out of 14 persons indicted.) Needless to say, the length of sentences against Albanian defendants are higher than those against Serbs.

The ICTY sentenced between 15 to 22 years in prison the Serbia high-ranked war criminals—Milosevic’s immediate subordinates, Sainovic, Pavkovic, Lukic, Ojdanic and Lazarevic, for committing systematic war crimes and crimes against humanity in Kosovo, whereas the Specialist Chambers sentenced Salih Mustafa, a KLA senior official, to 26 years in prison for torture of at least six detainees and the murder of one prisoner.

According to Humanitarian Law Center in Kosovo (HLCK), UNMIK and EULEX filed 48 indictments throughout 1999-2018against 111 individuals: 25 indictments against Serbs, 19 against Albanians, three against Montenegrins and one indictment against others. UNMIK filed 10 indictments, three against three Serbs, six indictments involving 19 Albanians and one against one Montenegrin. EULEX filed 22 indictments: 10 against 11 Serb defendants, 10 against 39 Albanian defendants and two indictments against one Montenegrin and others. Overall, international justices indicted 61 Albanian defendants as opposed to 44 Serb defendants, five Montenegrins and one defendant belonging to others, convicted 34 Albanians as opposed to four Serbs and one Montenegrin (final judgements), acquitted 23 Albanians, 13 Serbs and two Montenegrins. Out of 28 suspects/persons at large, 24 are of Serbian nationality.

The data is controversial, though. UNMIK, as Amnesty International reported, completed just over 40 war crime casesagainst 37 individuals, leaving behind a backlog of 1,187 cases to its successor, EULEX. Of these cases, 21 were brought by Albanian justice authorities against Kosovo Serbs arrested and detained for war crimes in 1999. By mid-2002, 19 of these cases were completed: the majority of defendants (Serbs) were acquitted by international panels, while the majority of subsequent cases prosecuted by UNMIK were brought against ethnic Albanians for crimes against other ethnic Albanians. In total, the UN mission, asUNMIK’s spokesperson Sanam Dolatshahi says, investigated and/or tried 18 war crimes cases. Which means an average of two cases per year.

EULEX, according to spokesperson Ioanna Lachana, issued 22 indictments, including two indictments in cooperation with local prosecutors, and convicted 38 out of 41 defendants convicted for war crimes in Kosovo. An average of two cases per year. When EULEX ended its mandate in June 2018, it handed over to Special Prosecutor of Kosovo 434 war crime police case files, including missing persons’ case files, judicial case files and more than 1.400 prosecutorial case files. Prosecutors of Kosovo, on the other hand, filed 16 indictments: 11 against 29 Serbs and one indictment each against one Albanian and three Montenegrins. In the last two years, local prosecutors have been dealing with 14 cases against 12 defendants, and only last year, authorities arrested three persons in charge of war crimes in Kosovo.

Whilst Dolatshahi doesn’t make any comments relating to the number of cases based on the ethnicity of defendants and the smallernumber of Serb vs. Albanian defendants tried and convicted for war crimes, Lachana provides a number of reasons: the mission’s limited mandate—EULEX did not have jurisdiction to operate outside of the territory of Kosovo given that many suspects moved out when the war ended; lack of the law in absentia at the time when the mission was deployed, which prevented EULEX to proceed with war crime cases allegedly committed by individuals who were at large; and the unwillingness of Serbia institutions to cooperate with the mission to extradite Serb defendants who were born/lived in Kosovo.

In general, UNMIK and EULEX, based on the HLCK monitoring, issued 48 war crimes indictments against 111 defendants—with one final judgement by UNMIK and 22 by EULEX. To date, the international and local judges and prosecutors indicted 119 individuals, convicted 45, acquitted 41, and the process against six defendants is ongoing. As the above data illustrates, the number of Albanians/KLA members indicted and convicted supersedes the number of Serbs, members of Serbia and former Yugoslavia armed forces acting on behalf of the State, indicating that international justices in Kosovo had been biased, directed against Kosovo Albanians/the KLA members in their war crimes and crimes against humanity proceedings.

Serbia: The Culture of Impunity Prevails

IN SERBIA, on the other side, “there was negligible progress in bringing to justice” those who committed crimes illegal under international law. The highest state officials have continued to publicly challenge the judgments of the ICTY and provide support to and public space for convicted war criminals. Although the government adopted the 2016-2020 National Strategy for War Crimes Prosecution aimed at investigating and adjudicating high profile cases, no significant progress on war crimes prosecutions has been made, the HLC in Serbia found in 2019. The charges against high-level perpetrators are absent—with no indictments filed against high-ranking perpetrators so far. The EU Commission evaluated as “very weak” the 2016-National Strategy rate of implementation,demanding from Serbia to prioritize complex and high-ranking officials’ cases, as well as provide a clear legal approach to resolving the issue of command responsibility.

Based on the existing data, the OWCP has completed 52 casesagainst 212 individuals, convicting 54 defendants, including one person relating to war crimes in Kosovo (Prizren case) and acquitting 49 others. (The website of the OWCP, whose data I am referring to, is currently under maintenance). In four years of the 2016-National Strategy’s enforcement, the OWCP, according to the UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights Fabian Salvioli, issued 34 indictments against 45 defendants (the majority of them transferred from Bosnia and Hercegovina-BiH), and 17 indictments following the implementation of the 2021-2026 National Strategy for War Crimes Prosecution: seven in 2021 against nine defendants, of which four cases were transferred from BiH (two of them high-ranking criminals) and 10 indictments in 2022. The Higher Court rendered five judgments in 2021, convicting six defendants, while the Court of Appeals rendered six final decisions, convicting sixdefendants. No defendants were acquitted (EU Commission, 2022). In the 52 indictments of the ZPKL against 238 persons, the conviction rate was 85 percent, 94 percent of the indicted were Serbian nationals. Momentarily, Serbia has a case backlog of 1,731 pre-investigative cases.

The OWPC has been subject to pressure and political interference—criticized for inefficiency and slow progress in investigating and adjudicating war crimes. The fact that the vast majority of indictments did not result from the OWCP’s own investigation but were transferred from the BiH Judiciary, according to HLCS, is an indication of the OWCP’s inefficiency. “If the OWCP continues to work at its present speed, over the next 10-year period it will solve only an insignificant portion of war crimes cases,” concludes HLCSin its report (2019).

In four years of the 2016-National Strategy implementation, meanwhile, the OWPC, as the HLCS notices, has not issued a singleindictment relating to crimes in Kosovo and failed to conduct an adequate and effective investigation into the Landovica case. The OWCP has taken over 952 cases from the courts of general jurisdiction in Prishtina, Peje and Prizren, of which 810 are against unknown perpetrators (2018). The HLCS has—since 2013—filed nine criminal complaints for crimes committed in Kosovo but none of the suspects had been subject to OWCP investigation by the end of 2018 (2019). Since the OWCP does not have de facto jurisdiction over the territory of Kosovo, it is unable to investigate crimes and prosecute alleged perpetrators residing there.

As a matter of fact, the cooperation between Kosovo and Serbia on war crimes has stalled since May 2014, when the responsibility for war crimes investigation was transferred from EULEX to local prosecutors (HLCS, 2018). In reviewing cases relating to war crime in Kosovo, FDHK, as BIRN reports, found that the cooperation between Kosovo and Serbia on 14 war crime cases was absent. The same number of cases had been investigated by the Hague Tribunal, as well—a too small number compared to the gravity of crimes committed by Milosevic regime in Kosovo: 13,535 persons were killed, 862,979 others were forcibly deported, 6,024 were reported as missing, and supposedly 20,000 women were sexually abused.

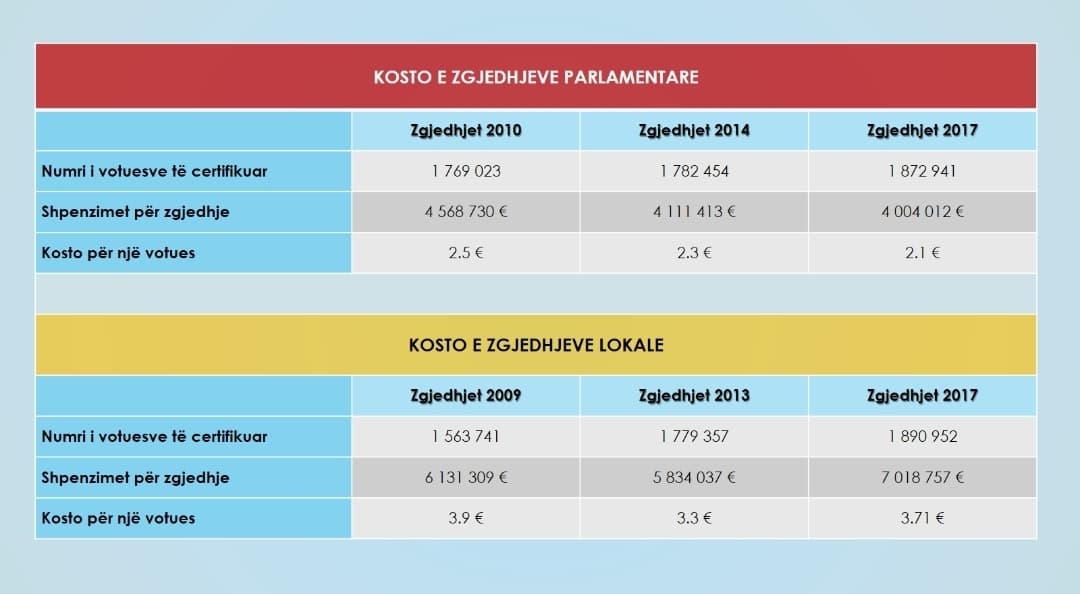

Table 1.1. Cost of Parliamentary Elections in Kosovo, 2010, 2014, and 2017. Source: Kosovo Central Commission.

Table 1.1. Cost of Parliamentary Elections in Kosovo, 2010, 2014, and 2017. Source: Kosovo Central Commission.

You must be logged in to post a comment.